The Empress & The Moon Rabbit, Part I: Weaving the Silk Map

Textile Diplomacy in Han Dynasty China and the Byzantine Empire

Happy November Full Moon, everyone!

Full Moons here at Moon Rabbit Musings are dedicated to illuminating the interconnected pathways of history, culture, and spiritual thought along the Silk Roads.

Together with Madeleine from

, we’ll be exploring an instance from history that converges our fields of study and provides a perfect reason to set off this first-time collaboration. Of course, this event is the organised intrigue of the Byzantine Empire to steal silkworm eggs from China.If you’ve been here for long enough, you know that Silk Road history is made by the correspondence of its tributaries across space and time rather than singular, linear events told through one perspective. Through one event - two monks smuggling silkworm eggs onto the road - larger themes of identity, silk’s gendered reception, and the way it formed diplomatic relationships, begin an intercultural dialogue, echoing parallels and surfacing contrasts as we wrote our parts.

Tonight, the caravan’s load is heavy. Spanning from as far to the West as the Empire of this Empress, and as far to the East as this Moon Rabbit’s impact, we present you a carefully woven map of silk.

In this first part, we will cover much of silk’s meaning and culture in Han Dynasty China, before moving to what prompted the Byzantines to hatch the mission to attain silk, and how its symbol and currency unfolded from there.

You’ll hear of its origins. Almost an element in its own right, silk shines like water in moonlight, formed from moths never born.

Let’s roll out the map.

The Universe in Silk

In a single meter of silk, the infinite universe exists; language is a Great Flood from a small corner of the heart.

— Lu Chi, Ars Poetica

I’m not an expert in Chinese culture. Yet to my understanding, both culture and its action - cultivation - are at the heart of Chinese identity. Cultivation is defined by preparing the land for growing crops. Characterised by actions of refinement, improvement, practice, and timing, its Chinese translation, 修行(xiū xíng) - literally means restoring or correcting form, and was transferred onto the cultivation of character from its original meaning in agriculture.

Silk is one of the oldest symbols of this. Its craft, meaning, and, of course, its globally recognised value in socio-economic environments that carved the way for the Silk Roads in the first place. Silk was not only the initiator, but an ongoing “sponsor” of the Road: beyond its meaning as a commodity, it was a currency. At times, in place of gold.1

There are many reasons why silk is so valuable from a strictly material point of view. A single cocoon can unfurl a thread of up to 1300 metres, but the threads of several cocoons need to be twisted together in order to create a stable enough thread to be processed in looms.

Yet, the materiality and spirituality of silk is anything but mutually exclusive.

Crafts weave consciousness. Thread by thread, silk has been spun into a fabric that carries the most sacred of things: bodies, scriptures, wishes the deceased take into their next life. As a symbol for rebirth, the silkworm predates the Buddhist Wheel of Life. As a textile, silk indulges luxury, wealth, and power: all that is glory, manifest on earth.

Mother of Silkworms

It remains unclear how many millennia before the common era people started to make silk. Recent archaeological findings suggest biomolecular evidence of silk fibroins in tombs excavated at the neolithic grounds of Jiahu, located in present-day Henan, North China, dating back 8,500 years.2

Although different versions exist, there is one woman that’s credited with the discovery of silk and the invention of the loom: Leizu, sometimes referred to as “Mother of Silkworms”, Empress wife to the mythological Yellow Emperor, who is likewise associated with a myriad of inventions that form pillars of Chinese culture.

Story has it that a silkworm’s cocoon fell into Leizu’s tea, who soon found a beautifully soft and unending thread spinning from her finger.

As with many of these tales, they are meant to create a direct relationship between people and folk heroes. Leizu is depicted as a benevolent ancestor, a perceptive character that generously shares her discovery with the people, and those that come after.

Either way, it resulted in the breeding of silkworms and the growing of their only accepted food source - fresh mulberry leaves. In combination with the processing of threads, this highly time-sensitive body of crafts is known as sericulture.

“Men plow, women weave”

Perhaps because the origins of sericulture are so connected to a female figure, sericulture was a gendered undertaking. There is a Chinese proverb: 男耕女织, nán gēng nǚ zhī; men plow, women weave.

Women did not only weave silk. From the picking of leaves to the rearing of worms, reeling of silk to the actual of weaving and dyeing, the actions of sericulture were taken on by women of all ages. Each step required a specific skill set that placed those that were most experienced above those that had to learn. Silk production manuals from much later, when silk production spread westwards, lay down the steps in excruciating detail:

For instance, silkworm eggs have to be kept at precise temperatures until they hatch — and once they do, have to be fed with fresh mulberry leaves every half hour, even throughout the night. And this is just until they form cocoons.3

By having a place in sericulture, women took on an important economic role in early Chinese society, allowing them to contribute to the wealth and status of their family, and by extension, their stately organisation.4 Hence, the proverb might actually express complementary relationship rather than a subordinate one.5

Although sericulture is often framed as a “secret” that was held in China for centuries, its complex craft and societal structuring raise the question of whether anyone could actually copy, and uphold, a systemic and quality production anywhere else. Eastwards, it had been done: knowledgable “immigrant” workers were implored in Japan via Korea, where silk production had been introduced earlier.

But westwards, the challenges looked different: the climate, the territory, the agendas of other Empires dominating trade.

Granted, the Byzantines weren’t the first to attempt the theft of silkworm eggs. Some hundred years before them, legend has it that a princess hid silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds in her headdress, before setting off to the Kingdom of Khotan in West Asia.6

On the surface, it appears that the Byzantines had enough sources to acquire silk from; China’s silk “monopoly” had already been broken. Why, then, take a risk that could cost your head?

Let’s hear from

on that matter.The Great Byzantine Silkworm Heist

In the middle of the 6th century, during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, two monks undertook an extraordinary journey. They ventured from India to Constantinople, back to India, and then, apparently, to China.

Why?

Well, during a period of heightened tension and war between the Byzantines and their neighbours, the Sassanian Persians (c.524-532 AD and from 540-562 AD), whose core territory lay in what is now modern Iran and Iraq, Justinian decided he’d had enough of the Persians being able to manage the economically and culturally lucrative silk trade. Silk flowed into the Byzantine empire from the East, following the multitude of roads, paths, sea-routes, and other winding ways that encompassed the Silk Roads.

Procopius, court historian of Justinian’s reign, recalls the almost unbelievable tale in his History of the Wars:

‘At about this time certain monks, coming from India and learning that the Emperor Justinian entertained the desire that the Romans should no longer purchase their silk from the Persians, came before the emperor and promised so to settle the silk question that the Romans would no longer purchase this article from their enemies, the Persians, nor indeed from any other nation; for they had, they said, spent a long time in the country situated north of the numerous nations of India—a country called Serinda—and there they had learned accurately by what means it was possible for silk to be produced in the land of the Romans.’

— Wars VII. xvii

These two enterprising monks had transported the eggs of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, all the way along the Silk Roads to Byzantium. Their journey began in India, a place which was not unknown to the Byzantines. Where the monks themselves hailed from remains unclear — the fact that they seemingly sought out the emperor, and were called monks, suggests they were Byzantines, perhaps Egyptian monks, from a monastery near the Red Sea, an area with known trade connections to India. Alternatively, they may have been Ethiopians, from the Axumite kingdom, another region known for international trade connections, especially for the trade in silk.

The tale intrinsically reveals the extent of Byzantine knowledge about the Eastern hemisphere. India was a known quantity, having been reached by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC, a feat that was immortalised in the many stories and legends about him, as well as in the continual flow of trade, ideas, and people between Greek, Roman, and then Byzantine territories and India. A level of direct trade between the Byzantines and India has been pretty firmly established.

Using the Muziris Papyrus, dated to the the 2nd century AD, Rathbone has demonstrated, pertinently for this analysis, that Chinese silks were brought to Roman Egypt by way of the Red Sea, having been picked up in India, along with a huge number of other items in the cargo.7

It is probable, then, that these monks had been in India to purchase silk and had stumbled upon the information that had became so valuable to Justinian, that the secrets of silk cultivation could be found in the lands to the North.

What lay beyond India was a mystery. The ‘northern’ nation of ‘Serinda’ may be taken to be China proper, perhaps modern Nepal and Tibet, or even Central Asia. All of these regions were central nodes of the Silk Road.

What is most clear is that the Byzantine silk heist was primarily driven by a desire to bypass Persia’s influence over the trade. This can be confirmed by an earlier story in the Wars, in which Procopius recounts Justinian’s efforts to make ‘common cause’ with and between the Ethiopian Christian kingdom of Axum and the Yemeni Jewish kingdom of the Himyarites.8

Although Justinian’s efforts were unsuccessful, I think this is a fascinating, early example of how the Byzantines would eventually come to consider silk and the silk trade: as a form of textile diplomacy, like it had been practised by the Empire that originated sericulture.

Even though the Byzantines did not have full control over the silk trade, not yet aware of the secrets of silk cultivation, they still leveraged whatever resources they could in order to profit from silk. It is clear that the use of textile diplomacy reflects the intense demand for silk in Byzantine society, the desire to control it stemming from economic and geopolitical practicalities as well as ideological necessities. Ideologically, silk’s rarity, exoticism, and the general extremity of the work to reward ratio, birthed a product that was as much a commodity of the imagination, a commodity of desire, as it was a purely economic one.

One of the most captivating snapshots of the silk-fine ties binding Byzantium and China can be found not in the stories of silk, nor of the stories contained within it. Rather, it can be found in the archaeological numismatic record: Byzantine gold coins, found in Chinese tombs. Two found in the tomb of a notable from the Western Wei Dynasty, Lu Chou, who died in 548 AD, date to Justinian’s reign. To me, these coins show the odd, pulling tension that existed between Byzantium and China, twinned poles of the world at this time, connected only through the exchange of their goods, and of loose ideas about the other. And, of course, by endless threads of silk — a connexion soon to be made all the more complicated, though never broken, by the Byzantines gaining the ability to cultivate the silkworm and its product themselves.

Throughout Roman and Byzantine history, silk’s imaginative capacity, the meanings encoded into the very nature of its fabric, held sway over literary forms and political discourse, over the visual arts, and over cultural practices, such as gifting. This made silk a rather complex feature of Byzantine artistic, economic, social, and cultural production.

An Introduction to Byzantine Silk Practice

Even though the secrets of silk production did not reach Byzantium until the 6th century, the Romans and the Byzantines had prized the material for its richness, suppleness, and shine for centuries. The importance of silk, and the professions associated with its manufacture, is attested to not only in the material record, but in the written one too.

Legal sources testify to the desire to control the silk trade from the Imperial Roman period. By Late Antiquity, we can find some laws on silk being codified in the 4th-century imperial legal compilation known as the Theodosian Code, (c.437 AD). Of particular interest is Theod.Cod.10.20.13, issued by the Emperors Arcadius, Honorius, and Theodosius II, which confirms the importance of silk as being imported as a raw material, not solely as a ready-made garment or cloth.

The emphasis on utilising raw silk, on having silk-weavers and dyers resident in the Byzantine Empire, was about ensuring a level of imperial oversight for a trade that could otherwise be unregulated.

The numerous classifications available for those working in the silk trade reveals how ingrained these industries had become four centuries after the monks’ had stolen the secrets of silk from China. However, the Book of the Eparch also reveals that the existence of domestic silk production by no means meant Byzantium was cut off from the Silk Roads and its continual flow of goods and people; even with the secrets of sericulture unlocked, there was still a desire to import goods from abroad.

Interestingly, Byzantine silks were considered premier by their Arab Caliphal neighbours. The Arab Caliphates, after the conquests of the 7th century, inhabited the territories formerly held by the Persians: Iran, Iraq, Central Asia, Egypt and the Levant. These were areas with the strongest connections to trade flowing from the Silk Roads, often representing the terminal end of one or all of the roads. The Caliphs and their subjects undoubtedly had access to Eastern silks, but the Byzantine hold on the trade had become so tight, their artisans so skilled, and, inevitably, the proximity of the Byzantine Empire to the Caliphates drove the costs down so much, that the western Islamic world was more than willing to accept Byzantine silk as the most desirable examples of the material.9

Byzantium had come to dominate the silk trade across the Mediterranean.

Twisted threads: Silk’s nuanced place in Roman, Late Antique, and Byzantine discourses

Silk’s immense beauty and desirability made it, of course, a prized possession. However, in a world before the cultivation of the silk worm’s threads were known, that also made it subject to scrutiny. Silk was associated in Rome and into Late Antiquity with a kind of effeminate, ostentatious luxury of the ‘East’ that many traditionalist writers, thinkers, and men of the state railed against. To be seen in silk was to embody the non-Roman, non-masculine ideals of indulgence and despotism.10

The onset of Late Antiquity saw some nuances folded into these views, however. For the writers of 4th and early 5th century panegyrics — a style of speech praising the reign of a particular emperor — silks were a fine thing to wear. Claudian, a fifth-century orator working at the courts of the Theodosian emperors, saw no issue with the young emperor Honorius wearing silks. However, these silks had to be heavy, and fall heavily, as opposed to the diaphanous, light, airy, and wildly expensive silks that highlighted the curves of a body. These heavier garments were more reminiscent of ‘appropriate’ Roman woollen clothing.

Women and silk: echos of one narrative

In the Christian period, declarations against silk took on a truly moralising tone. The early Christian writer, preacher, and rhetorician John Chrysostom, for instance, intoned against the wives of wealthy men who bedecked themselves in gold and silks. It was far more distinguishable and morally upstanding for a woman to dress in woollen garments, as these would reveal her humility, highlighting her inner — as opposed to outer — beauty.11

This decrying of elite women, typically the kinds of women who were patrons to early Christian writers, and their predilection for silk, led to some interesting developments. Perhaps the most important is the repeated attestation in the biographies and hagiographies of such women of their donations to religious foundations by way of silk. Important women such as Melania the Younger, a pious Late Roman lady, frequently donated their precious silken garments to churches. This was not only a means through which to express piety, however.

It is clear that silk formed part of these women’s ability to actively influence the direction of the church. Their ‘pious’ donations were accepted because these garments were not sinful when they were given to the lord — thus effecting a transformation in the material, which went from being associated with depraved luxury to true holiness. However, these early churchmen were aware that they were reliant on the economic status awarded to them by these women through their donations, and thus it seems clear that the women were expecting to have a say in what went on at these foundations, and what their legacy was to be in relation to that. Silk was the vector through which wealthy women transformed their reputations, and asserted their privileges, a model that continued well into the middle and late Byzantine periods.

Switch the pious Christian with stately Confucian duty, and you find some parallels in Chinese society, where the moral narrative sought to keep women in their place from the viewpoint of labor control. The Han Empire directly depended on the work of women in sericulture in order to carry out diplomatic strategies and fund military campaigns, and framed this fact with moral duty. In written records of the 2nd century, we find implications that women’s actions and work - as opposed to their appearance - were what made their identity. Wearing silk, on the other hand, was reserved for the Imperial family and high-ranking officials.

Stretching Silk Across the Mediterranean

As has been discussed, once the Byzantines possessed full control over the silk trade, the anxieties their Late Antique and Roman ancestors had experienced regarding its use and material nature faded. Nothing is more demonstrative of this than the role silks played in Byzantine diplomacy. Through a strategic network of gift exchange, the Byzantines effectively controlled their foreign policy through silk, forming marriage alliances, creating new allies, and ensuring the loyalty of old ones through the distribution of finely-woven and meticulously crafted cloths and garments.

By creating an independent sericulture, the Byzantine Empire was in a position to utilise silk as a currency in ways that the Han Empire had done before. Silk was now stretched, woven, and dyed to Byzantine ideas. But Chinese silk retained its distinct voice and expertise, which was never broken from its folkloric narrative. As part of China’s projected identity on the Roads, silk’s exotic pull carried on. But as a cultural identity, silk is the element through which a poetic kind of phenomenology unfolds.

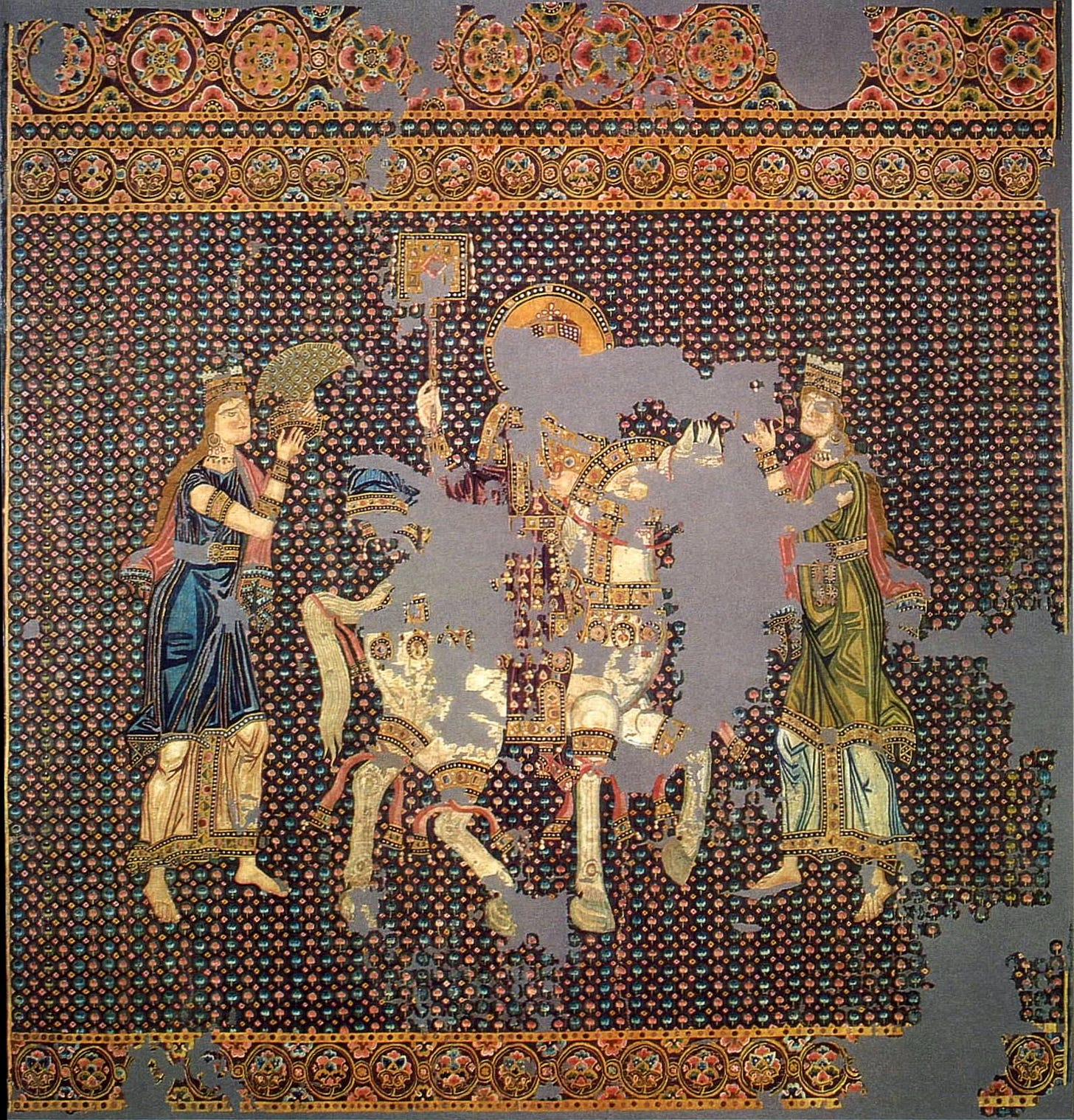

Next time at the Silk Road Sarāy, we’ll decorate the caravanserai with pieces og the most luxurious silks, comparing techniques of Byzantine and Chinese silk textiles in our favourite objects.

Meanwhile, don’t forget to check out Madeleine’s publication for more historical explorations on the Byzantine Empire.

Watt, J.C.Y., Wardwell, A.E., Rossabi, M. and Museum, C. (1997). When silk was gold : Central Asian and Chinese textiles. [online] New York: Abrams [Etc.], Cop, p.7. Available at: https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/62400/ [Accessed 6 Nov. 2025].

Gong, Y., Li, L., Gong, D., Yin, H. and Zhang, J. (2016). Biomolecular Evidence of Silk from 8,500 Years Ago. PLOS ONE, 11(12), p.e0168042. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168042.

Rothschild, N. and Mair, V. (2014). SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Rhetoric of the Loom: Discursive Weaving Women in Chinese and Greek Traditions. [online] p.2. Available at: https://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp244_weaving_women.pdf [Accessed 6 Nov. 2025].

Ibid.

Ibid.

BBC. (n.d.). BBC Radio 4 - A History of the World in 100 Objects, The Silk Road And Beyond (400 - 700 AD), Silk princess painting - Episode Transcript – Episode 50 - Silk Princess Painting. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1lLlDzzzpMCnw62GnrV7cLR/episode-transcript-episode-50-silk-princess-painting.

D. Rathbone, ‘The “Muziris” Papyrus (SB XVIII 13167): Financing Roman Trade with India’, in Société d’ archéologie d’Alexandrie, Bulletin 46, Alexandrian Studies II in Honour of Mostafa el Abbadi (Alexandria, 2001), 39–50

See: J. Howard-Johnston, Byzantium: Economy, Society, Institutions 600–1100, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024), p. 115

J. Howard-Johnston, Byzantium: Economy, Society, Institutions 600–1100, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024), p.110

B. Hildebrant ‘Christian Discourses about silks in Late Antiquity’ in Genito, B., and Liu, X., (eds.), The World of the Ancient Silk Road, (London: Routledge, 2022), p.511

B. Hildebrant ‘Christian Discourses about silks in Late Antiquity’ in Genito, B., and Liu, X., (eds.), The World of the Ancient Silk Road, (London: Routledge, 2022) p.515

Masterpiece of an article really ! Working myself on anthropology-related themes, this is a very interesting article !

A wonderful introduction to this silky collaboration! Fascinating and well-written.

@empressofbyzantium have you read Richard Fidler's 'Ghost Empire"? A deep dive in a very readable manner about "Byzantium", and by which he begins by denouncing the term.

"The 'Byzantines' themselves never used such a term - they called themselves Romans -but 'Byzantine' is just a name of convenience, coined (by historians) after the empire ceased to exist," Fidler wrote.