In English, the kami are usually referred to as “gods,” but what are they exactly?

“The first thing you need to know is that there are a lot of kami in Japan. In religions like Christianity, the belief is there is only one God. In Shinto, we believe that the kami are everywhere, and they are close to us. For example, they can be found in nature: in trees, rivers, mountains, on specific grounds and areas.”

From an interview with Shinto Priest Soushi, otherwise known as the Singing Shinto Priest (Yes, you read that right. Honestly, check out his songs).

Another interpretation of a Ghibli film? Why, you may ask - and rightfully so. Ghibli’s become the doorway through which we can escape from endless animation remakes and their potential to split society, into a world of nostalgia. A serene world, in spite of stories that centre around memories of war, destruction, and loss. But to answer the question, it strikes me that while we’ve managed to view a lot of these films through countless Western lenses - of story structure, cinematography, feminism - the philosophical roots of Ghibli films are mostly only brushed on ever so slightly.

So, in this series, I offer another approach to the world of Ghibli and soulful anime, tracing the imagery and symbolism to East Asian philosophy, and more specifically, I Ching hexagrams. I wrote an introductory article on the I Ching two weeks ago, so if you’re completely new to this, feel free to check it out! There’s much to unravel. If you’re interested in East Asian philosophy, history, and love anime magic, you have found the right niche.

In the unlikely case you haven’t watched this film, please do so immediately. Spoilers ahead!

A Calling and a Curse

Oracle: My Prince, are you prepared to learn what fate the stones have foretold you?

Ashitaka: Yes. I was prepared the moment I let my arrow fly.

Oracle: The infection will spread, cause great pain and kill you.

You cannot alter your fate, my Prince.

However, you can rise to meet it, if you choose.

Look at this. This iron ball was found inside the boar’s body.

It shattered his bones and burned its way deep inside him. This is what turned him into a demon. There is evil at work in the land to the West, Ashitaka. It’s your fate to go there and see what you can see unclouded by hate.

You may find a way to lift the curse. You understand?

With these words of advice, Ashitaka is asked to leave his tribe behind. This is where his story begins: by asking whether one can turn an infection upside down and resolve sickness through transformation.

At first, Ashitaka thinks that he does understand. Soon however, as he travels westward, he encounters aggression, destruction, and bloodshed. To outsiders, Ashitaka may appear like a detached stranger from an ancient, lost tribe. But we witness how his composed demeanour falters at the sight of Samurai raiding the land, setting villages afire and killing relentlessly. He discovers that there is strength in his infection, in the rage that takes over him.

And, there is a curse:

“Soon, all of you will feel my hate and suffer as I have suffered”

— spoken from the boar god turned demon that Ashitaka killed in the beginning.

Transforming Gods: Chinese Cosmology meets Shinto thought

Before we continue, I want to provide some context to why I’m utilising I Ching imagery to explore a Japanese film that draws symbolism from a native religion.1 The I Ching has a very specific and direct relationship with Shinto, the Way of the Gods (Shin = Gods, To = Way). This is a somewhat strange intercultural encounter: how do ancient teachings on Chinese cosmology end up matching with a local Japanese religion such as Shinto? Interestingly, the I Ching was reframed and published by a Shintoist, Yoshida Kanetomo, and a Zen master in Medieval Japan.2 This was in a later period of the Muromachi era, which is the historical setting Princess Mononoke is based on.

The curious interactions of Shinto with the I Ching were most prevalent during the Tokugawa period, however, and were basically going in two directions: in one, pro-Confucianists tried to include Shinto thought into the wider scope of Confucianism.3 Later, this direction was reversed. Shinto exerted itself as the indigenous religion of Japan, and hence, scholars of the late Tokugawa period tried to reframe the I Ching to fit Shinto narratives, while Confucianism was widely “discarded”. The I Ching, placing metaphysical relationships between the cosmos and nature/humans, seemed to share more with Shinto thought. Shintoists not only consulted the I Ching for divination, but implemented some of the concepts (like Yin and Yang as well as Five Elements), into Shinto rituals.

It may be because the I Ching, as well as Shinto, place emphasis on the forces of nature in a similar way. Though these forces are called trigrams/hexagrams or Ba Gua in Chinese, they do assert “divine presence” - that is, they carry intelligence, or the potential to change. In Shinto, wind, sun, rivers, lakes… become kami - gods or spirits - that resonate, mirror, and respond to human life. This interrelatedness of humans and kami, the way they constantly transform in and out of another, is also the starting point of Princess Mononoke.

With that in mind, are you ready to have the story of Prince Ashitaka unfold anew?

“I hate all humans” in a post-rage civilisation

Although tasked with observation, Ashitaka cannot resist becoming involved. Upon discovering Lady Eboshi’s village, he struggles to hold back from killing her. The words were clear: See what you can see, not see what you can do. He wasn’t sent westward to assassinate the villain, train as a saviour, and save the princess, even though he might feel inclined to do exactly all of those things. Being exposed to injustice to this degree - likely for the first time outside of his reclusive tribe - deeply troubles Ashitaka, no matter how well he might understand his task on a rational level.

Ashitaka’s motive “to see with eyes unclouded by hate” is ridiculed because it seems that in the civilised human world, everyone seems too busy gathering resources and manpower. No one here feels “hate” when they invent guns to take down creatures of the forest, they see it as a necessary measurement for expansion. Hate is what demons feel, it’s what San, the girl Eboshi tries to “save” feels - “I hate all humans!”. Ashitaka fails his own authenticity. After all, he is angry as hell, although he carries more than his own anger. When villagers retell the story of the boar being hunted down with guns, Ashitaka feels its hate, just as Nago’s curse claimed he would.

When Mononoke attacks Eboshi’s village, Ashitaka intervenes. But forcefully stepping between the two factions and pleading about how hatred is killing him doesn’t have the desired effect. He is shot. Wounded and on the brink of death, he is taken back to the forest.

Ashitaka survives as a favour of the Deer God himself, who stops his bleeding but doesn’t heal his infection. It’s not entirely clear if this is outside the Deer God’s abilities. The Deer God “gives and takes life” - which is in accordance with Shinto lore, where deer kami are seen as masters of death and rebirth. But Ashitaka’s case is one beyond the question of living or dying… there is a deeper meaning to surface in the words so crucial to his fate, one that he has to figure out himself.

So, what does it really mean to follow through with what the Oracle told him at the beginning? In a world stifled by war, injustice, and apathy, how does anyone manage to see with eyes unclouded by hate?

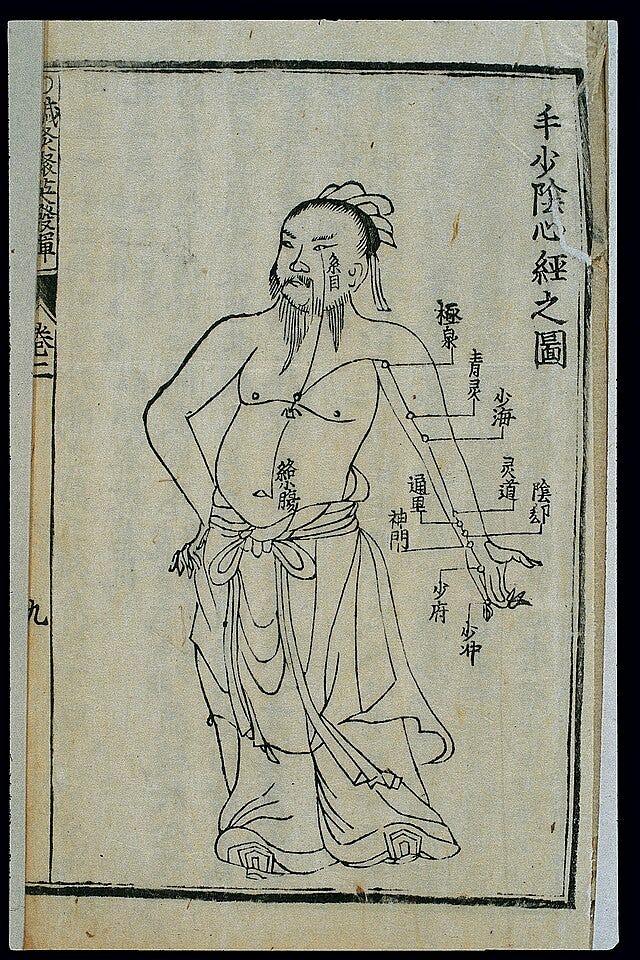

We have to take a closer look at the heart to answer this question. The heart is where the “spirit resides”. In East Asian medicine, the heart’s capacity is understood as enabling resonance and connection with our environment. That’s why the heart is sometimes likened to a lake or pond - when it is kept clear, it reflects. When it is stirred, it distorts. “Vision” therefore refers to what we can see clearly on the surface of our heart.

In Princess Mononoke, the lake later becomes the only place where the infection doesn’t spread, and water seems to be the only element that eases the pain from Ashitaka’s mark.

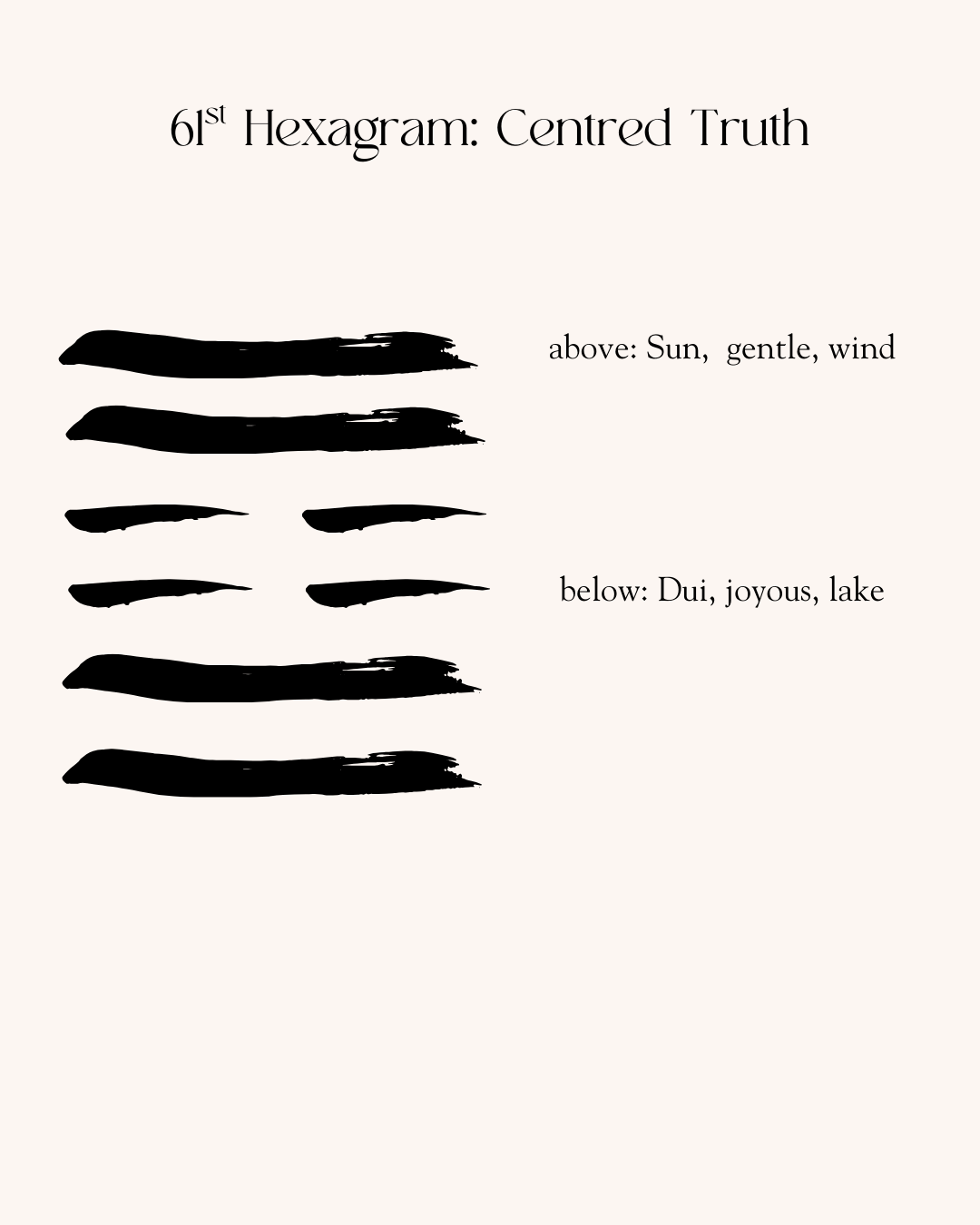

The hexagram that captures both the dynamic and resolution to Ashitaka’s conflict is expressed in Zhong Fu: Centred Truth (or more commonly translated as Inner Truth), the 61st hexagram of the I Ching. This hexagram consists of wind above and lake below. The lake symbolises joy, while the wind represents gentleness. When wind meets lake, there is a breeze that infiltrates even the most inaccessible spaces on the surface of the lake. It is a motion brought about by softness - as wind ripples across water, things begin to circulate.

The dynamic described in the commentary of the hexagram aligns with that of Ashitaka’s: the situation presents people and circumstances difficult to penetrate (=the people of Eboshi’s village, including herself, but also San to a degree). In such a case, force and aggression will be in vain. What prevails is soft infiltration: the ability to inhibit compassionate disengagement, to face and meet without being swayed.

At its centre, the hexagram holds two broken yin lines, symbolising an empty heart or eyes ’unclouded' , surrounded by firm Yang lines. As a strategy, this hexagram is about more than just “peacemaking” - as strategies generally do in the I Ching, this strategy addresses Ashitaka’s inner attitude. Therefore the name “Centred Truth”: the core idea is rooted in the empty space where the heart resides.

From an East Asian Medicine standpoint, there is a real connection between the eyes and the heart, since the heart meridian ascends to the eyes, where the spirit is said to open in them. In that same vein, I think it’s pretty clear that Ashitaka’s heart and liver are most affected from the sickness. The point of attack from which the infection enters Ashitaka’s body lies in the right arm. With this close proximity to the chest, the heart is obviously part of the danger zone. The poisonous nature of the infection affects the liver’s ability to purify blood. In terms of East Asian Medicine, this leads to an accumulation of heat toxins. The liver in particular, and especially in combination with rising fire, is associated with rage — the core emotion of Nago that clouds Ashitaka’s vision, and San’s as well.

When you have an infection that poisons you from the inside, creating heat toxins that lead to liver and heart fire, nothing is harder than keeping your heart calm and impartial. It is the forest that facilitates this inner progression to “Inner Truth”, or specifically, the heart of the forest, which is the sacred area only walked by the Deer God.

In this place, a specific kind of emptiness is illustrated: the heart of the forest is a tranquil collection of sacred lakes. It’s a place where the buzz of life gives way to stillness and reflection. Here, where Ashitaka’s life is restored, we can see how the serenity of existence imprints on him and, in turn, teaches him how to empty his heart.

Protecting Emptiness

While in the beginning, Ashitaka seems concerned with looking for everything that’s “wrong” with the world, upset about the fact that his moral values don’t matter to people like Lady Eboshi, he experiences a world beyond morality in the forest. Within its grounds, demons and gods wander alike. The Centred Truth of the forest is where all living things exist on the periphery, while existence itself becomes pure essence—water, tree, wind.

The forest is not only where Ashitaka’s body comes back to life, it is also where he falls in love. These experiences become Ashitaka’s True North, the place in his heart that knows, the place from where he navigates everything else coming his way.

Ultimately, even as the battle escalates, he remains tenacious in protecting his heart, and by extension, the heart of the forest, where some of the crucial scenes towards the end of the film take place. Unswayed by hate, he prevails in compassion. He realises that without safeguarding this emptiness, this “uncloudedness,” he loses his compass for action. By releasing his rage, he uncovers the root of his disease. Similarly, by nurturing his empathy, he perceives the same cursed, destructive patterns in those around him, most notably San. From this new found emptiness, without aggression or force, he is able to hold up the mirror to her: you are human, and so am I.

The heart of the forest is an outer manifestation of Zhong Fu — Centred Truth. This outer manifestation inspires Ashitaka’s heart to grow in the same manner, by cultivating a space that clears through gentleness, and allows for soft circulation through emptiness.

Invitation: Wind above Lake

This is another invitation for you to explore. Imagine the place where you would be brought back to life. Can you connect to an inside place, perhaps modelled after a place you’ve been to or want to go to, where you feel peaceful just existing?

Notes and Further Reading:

Japanese and Chinese culture share a lot of history. It wasn’t until the (late) Qing Dynasty that the Sino-Japanese relationship truly began to crumble. In the aftermath of World War II, the chaos brought about by the Cultural Revolution and continuous tensions between the Japanese government and the People’s Republic of China, combined with the the bad blood that history collects and forgets, we tend to play this bond down. Daoism and Confucianism, two of the most popular schools of thought that developed from the I Ching, have impacted and shaped Japanese culture in a steady dialogue with native ways of indigenous Japan.

Ng, Wai-ming. “The “I Ching” in the Shinto Thought of Tokugawa Japan.” Philosophy East and West, vol. 48, no. 4, Oct. 1998, p. 568, https://doi.org/10.2307/1400018. Accessed 8 Mar. 2021.

see above.

this is brilliant. i would LOVE to learn more about different cultures and interpretations of other Ghibli films as well, i wish i had come across something like this earlier considering how long Ghibli movies have been around. i spent my childhood watching them! thank you for this, lots of love x

Fascinating! I didn't know about the connection between Shintoism, I Ching, and Confucianism. Looking forward to learning more.