Once, a rabbit’s pure heart was rewarded by a place on the moon. In quiet lunar garden, it has since pounded herbs to elixirs, mortar and pestle in hand. Where the rabbit brews, musings rise: steeped in starlight, a lunar thread tied to earthly things.

Welcome to Moon Rabbit Musings. Happy pink spring full moon!

Whether you found your way here on your own or because I asked you to — thank you for being here! Chances are that I’ve considered you a part of my journey and thought you’d be interested to see how I’ve begun to weave, creatively, all the good things that have found me in recent years.

I’m almost one week from opening my practice & studio in Berlin Prenzlauer Berg. Inspired by old forms of healing & bath houses, this place is growing into a space where healing arts and creative unfoldings meet. Should that venture interest you, feel free to check out my new website here (events and subsections coming soon)!

In the story of the Jade Rabbit (yù tù - 玉兔) according to Chinese legend (there is a Jātaka version linked below), a poor, starving hermit wandered the land. Ragged and hungry, he settled by a fire to retire for the night. On his last quest for food, he came across three animals and asked them for help: a fox, a monkey, and a rabbit. He was offered a fish by the fox, fruit by the monkey, but the rabbit, alas, unable to find anything, offered itself: it leapt into the fire and so intended to make a meal of its own flesh.

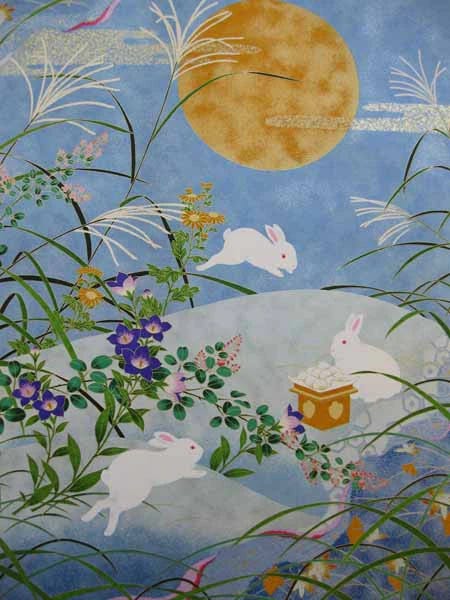

Stirred by this selfless act, the hermit, who turned out to be no other than the Jade Emperor in disguise, rewarded the rabbit with a place on the moon. Bestowed with mortar, pestle, and divine knowing, the rabbit pounds herbs to miraculous elixirs of immortality as the moon waxes and wanes.1

When I revisited the story, my first thought was: Oh, boy, here we go again, another tale of female sacrifice. It was, of course, a projection. The rabbit’s gender is neither mentioned nor relevant. However, having heard enough stories of female sacrifice (from both Western and Eastern cultures, by the way), I got a bit tired of the sacrifice theme altogether. You’ll come to understand my gut reaction when I’ll elaborate on the story that I’m still trying to somehow resolve — the strange and gruesome tale of Princess Miaoshan.

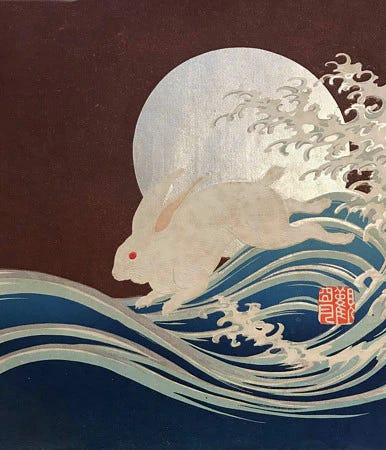

Thankfully, with this story, I came to terms. The image of the rabbit and the moon is so ingrained for many of us with an East Asian background that it’s impossible to separate the two. The rabbit is not only a Chinese zodiac sign, but a divine figure in China, Japan, and Korea. While usually, big and mighty animals are admired and channeled for their bigness and mightiness - a lion’s heart, a bear’s strength, a dragon’s power - a rabbit seems like a curious exception. The rabbit, unlike the dragon, the wolf or the bear, does not possess “divine” properties that make it the protagonist of a culture’s or a city’s creation story. Why then, divine?

In my recent travels to Japan, I accidentally stumbled upon the Okazaki-jinja shrine in Kyoto. The gate caught my attention on my way to the Philosopher’s Path, and upon entering next to a large tree, one sees the city as through the edge of a forest. There’s a playful kind of serenity that unfolds as rabbit statues are scattered throughout, showing up like hares on a meadow.

Close to the shrine’s heart, people hang wooden plaques (ema), guarded by an upright black rabbit that seems to take in the hand-written notes of those praying for the delivery of a healthy child, a good birth, the blessing of a family. Another pair of rabbits is found on the shrine’s other side, where a conscious act of attention is supposed to bring luck to all matters in love and relationships.

There’s a resonance through time to the inviting, approachable nature of the rabbit. The rabbit brings out the soft side in us, our delicate wishes and ponderings on love. If you let your mind sink into the image of a basket full of baby bunnies, you’re probably notice how something in you will soften (serial killers excluded). In turn, what can be offered to the divined rabbit aside from untold inner yearnings, is our attention and care for the tenderness of the ordinary.

Notice how most of the heart-wrenching love confessions are all about celebrating the daily or appealing to the return of the ordinary: “In another life, I would have really liked just doing laundry and taxes with you” (Everything Everywhere All At Once, 2022 — forgive me for quoting a totally subjective and random favourite). It is perhaps because devotion to the ordinary is viewed as the purest expression of love: love not proclaimed, but lived in action to the smallest areas of life, as it resets and repeats, over and over.

Within this circular motion, the rabbit and the moon actually form a harmonious pair, as the moon reflects the cyclical nature of life: the call and return within ebb, and flow. The “mystical elixirs of life and immortality” which the Moon Rabbit is the master of, perhaps refer to its skill of expanding devotion into the rhythms of life. It is a total power of Yin: a dynamic with attraction, not aggression, that never dies down.

Nevertheless, Yin is only understood in relation to its counterpart. So what would the relative power of Yin be? What is the Yang aspect in relation to the Yin in terms of the rabbit?

We have to look at the season of spring in order to understand this relativity. In Chinese Five Phase Theory (Wu Xing), this season is associated with the element of wood. Spring, in Eastern as well as Western worldviews, is a time of growth and renewal which traditionally is seen as Yang. However, this generalisation leads to the understanding that Spring = Wood = Yang, which is untrue. As masters of the relative, East Asian cultures almost never see things that way (see what I did there?). Fertility is the result of Yang igniting Yin — the alignment of complementary aspects.

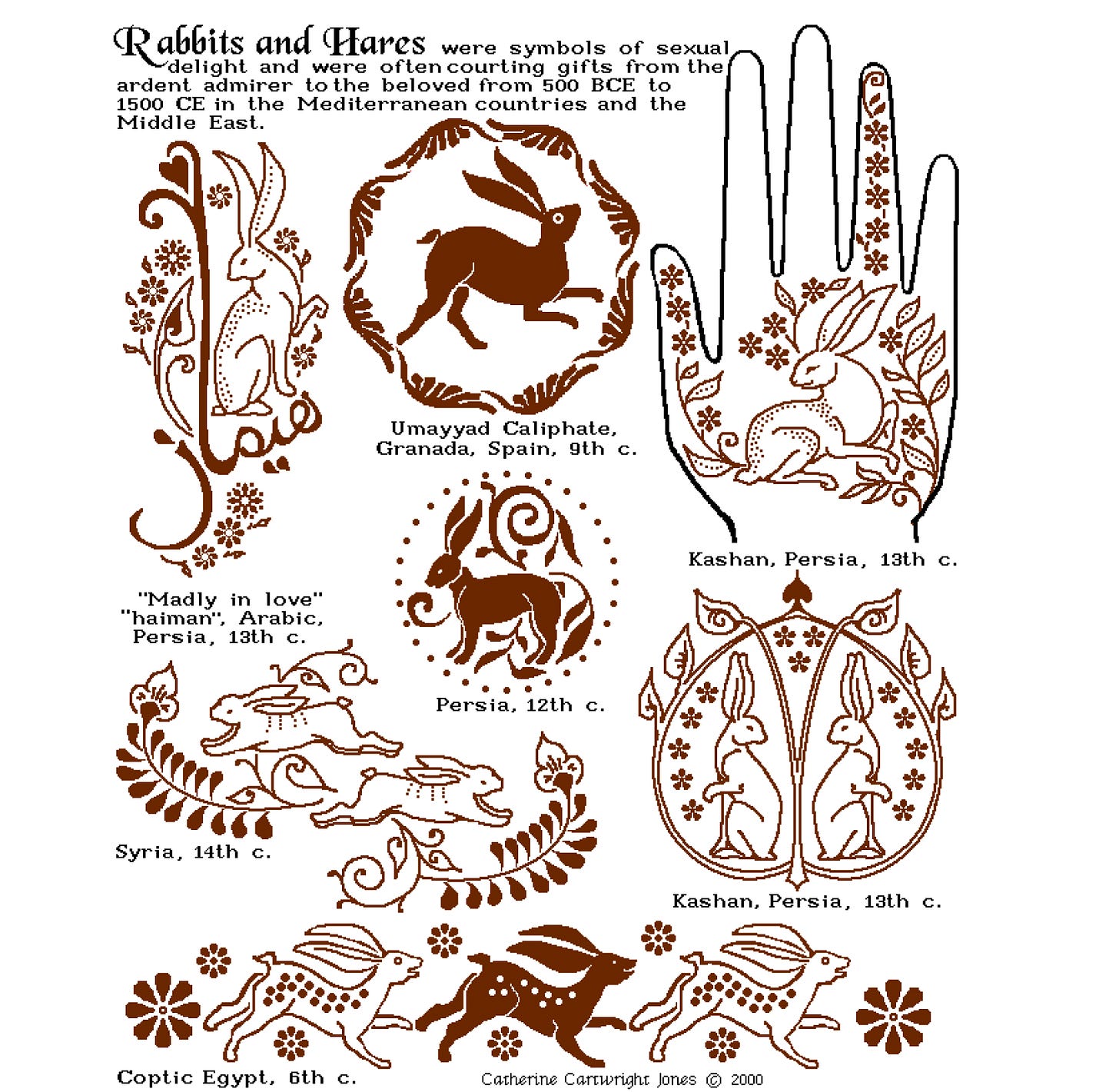

Interestingly, the Yang aspect of the rabbit is quite prevalent in Western culture. While the Moon Rabbit hangs out with Moon Goddess Chang’e as part of the lore, the Easter Bunny, less mythic companion, more commercial emissary, becomes a most central symbolic figure for Jesus’ resurrection anniversary. Ironically, dead hares and rabbits formed a popular subject of Dutch and Flemish baroque still life paintings (can someone muse on why?).

And of course, there’s the whole “sexy bunny” theme, heavily influenced and commercially branded by Playboy in the 50s. In a far more emphasised manner, the rabbit’s qualities are extracted, projected and sexualised. We all know that rabbits procreate a lot. But there are actually some insightful scientific explorations on rabbit fertility and sexuality that not only confirm a lot of East Asian rabbit lore, but could help us fine-tune our perception on conception in general.

Rabbits, as it turns out, don’t ovulate spontaneously as most mammals (meaning most mammals, including humans, ovulate “on their own endocrinal arc”, without needing to mate). Instead, they ovulate through stimulation — mating triggers the hormonal cascade, which usually takes around 10 hours.2 There’s even a study suggesting that the female rabbit needs to experience some kind of orgasm to ovulate.3 As if that weren’t radical enough, rabbits can become pregnant again mere hours after giving birth, and in a single mating season, may produce up to 30 offspring.

In that light, consultation with a rabbit for love and child making feels less like symbolism and more like biology winking.

In terms of Yin and Yang, the rabbit’s rapid-paced fertility illustrate Yang dynamics within its overall Yin-quality. Hence, in classical Chinese viewpoints of cosmology and nature, the rabbit is associated with the second phase of spring. The rabbit symbolises the power of soft spring, which sounds like a seasonal colour analysis subtype, but refers to the Yin balance that the rabbit strikes in a Yang-dominant season. This “Yin” phase of spring is still about growth and fertility, but different from its initial burst. After the surge that rekindles the metabolism of nature (purging, cleansing, igniting), the second half of spring cultivates the abundance with the balance of night and day (spring equinox), the begin of mating seasons, the rise of scents from flowering trees. And of course, the rain.

Let’s return to our Chinese tale in the opening. While my first thought was rubbish, on second glance, it stood out to me that the rabbit wasn’t divine as in the great-creator-is-divine-because-he’s-the-great-creator — but because it became divine. A selfless act, or a true act of devotion, can only be attributed as such if it comes from the heart. The rabbit of the story, the Moon Rabbit in question, rose to divinity for its pure-heartedness, not for conquering and creating. And that I can find nothing wrong with.

In fact, I’ve rather obviously dived right in. But perhaps that’s the point. From the mortar and pestle of story, memory, and medicine, I’ll be offering what I can. These Lunar Letters are my way of learning to move with the tides, curious what the Moon Rabbit might muse on as the light waxes and wanes. With each turn, I hope to absorb a little of that fluid wisdom. Who knows — maybe one day, I’ll learn to fall in love with folding the laundry.

To conclude, I’d love to know: what love scene lives rent-free in your heart? The softer, quieter kind. Do you have a favorite ‘laundry and taxes’ moment?

And, speaking of rabbit-related yin powers — is there a totally mundane or ordinary thing you’ve fallen in love with? One that calms your heart? Mine’s resetting the kitchen at the end of the day (which was a slow burn, so I guess my hopes for loving to fold laundry are still up).

Also— the third’s alsways a hot question, if you could choose your ovulation pattern, would you stick to spontaneous ovulation (as in humans), or does induced-ovulation sound better?

Notes and Further Reading:

Mattioli, Simona, et al. Physiology and Modulation Factors of Ovulation in Rabbit Reproduction Management. Vol. 29, no. 4, 29 Dec. 2021, pp. 221–229, https://doi.org/10.4995/wrs.2021.13184.

Walton, A, and J Hammond. “Observations on Ovulation in the Rabbit.” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 6, no. 2, 1 Dec. 1928, pp. 190–204, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.6.2.190. Accessed 21 May 2024.

Overview over the history of the Moon Rabbit in India, China & Japan:

Shoji, Daigo. “月の兎の起源と文化 (History of Moon Rabbit) - Moon Rabbit in China.” Google.com, 2015, sites.google.com/site/moonrabbitenceladus/moon-rabbit-in-china?authuser=0. Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.

When I was teaching I found this great picture of the moon ( a nasa picture i think) that clearly showed an outline of a rabbit!!!

as for laundry and taxes, the whole movie! esp when Evelyn just transforms into so many characters seamlessly, when Joy really inhabits the Jobu Tupaki, persona, the sausage fingers, and when sweet Ke Huy Quan just always protects his wife, regardless. Wonderful movie!