Threads of Silk & Sound: The Many Lives of an Ancient Lute

A new moon listening invitation to Silk Road music & crafts, reinvented.

August 2023, Beijing, China

Visited Cao Wei Dong’s Workshop today, he’s not only making instruments, he’s recreating a specific type of string instrument from the Tang Dynasty, and I don’t know, I feel… relieved?

There’s a silent fascination I carry for the traditional crafting of string instruments. The makers, with their commitment to carving, honing and tuning a body of wood to hold sound reach a restless part in me. The tradition of forming these instruments is intimate — between our hands and the science of wood only. There is no interference of heavy machinery and no space for a mass-produced scale that should require a kind of compromise. In the absence of robots, there is another type of technology enveloped in the craftsmanship of instrument-making, one as alien and as akin to dying stars still showing on the night sky. Each piece is a process as much as an object. Yet without the continued work of human hands, the most intricate instrument will always remain mute.

This is a new moon exploration on an exquisite object carrying magic, history, and orally transmitted craftsmanship all at once, and a new addition to the Silk Road Sarāy — a fresh section dedicated to the abundant wonders of stories & objects you could have encountered at a caravanserai during the golden era of Silk Road trade.

Like many merchants and travellers themselves, tonight’s object has evolved so much by journeying the Silk Road that its true origins are muddied. In its 2000 years of history, it has reached peak prominence at China’s imperial Tang Dynasty court some 700 years into its existence. Since then, it has adorned the body of celestial dancers in cave murals and become the attribute of the Great Grandmother of the West - Xi Mu Wang, the goddess who grows peaches of immortality in her garden in the far West of Kunlun Mountain.

Any idea which instrument I might be referring to?

It has a funny onomatopoeic name on top of that.

It’s called pipa. A “traditional Chinese solo and ensemble instrument” — only that it isn’t. There’s much more than meets the eye.

Sandalwood, Fish Glue & Strings of Silk

Shaped like a pear, the pipa produces sound via a bridge made from bamboo in the lower part of its body. Through its vibration, the surface board resonates, producing sound when a string is plucked, and different tones when the string is pressed down on the frets spread across the body.

The main wooden body is carved from a single piece of wood and much shallower of that of a guitar, for instance. Precious woods such as rosewood or sandalwood were used for the body, while the sound board is usually made from paulownia. Fish glue is applied to hold the main parts of the body together. The pipa is then tied with rope to hold everything together and left to rest.

Rising from the neck, the head curves and arches back and front, usually in an s-shape and opening into a sophisticated face providing a small canvas for individual artistic craftsmanship. The neck/head curve also contains four to five tuning pegs holding the upper end of the string.

Traditionally, the pipa head was rounded, angled or shaped into specific symbols like the auspicious ruyi. They were painted with buddhist imagery from scrolls or lined with peonies carved from bone.

Due to the contracting and swelling of wood with time, and impacted by climactic factors, traditional craftsmanship requires a pipa to rest several years in between the stages of its making. Cao Wei Dong, one of the most devoted pipa makers of our time, takes up to 15 years to complete a pipa, with resting years for up to a decade. Because the craftsmanship is not a handbook, but was passed down in oral tradition from generation to generation, we might also consider the timing of pipa-making in a philosophical and cosmological sense. Natural cosmological cycles like zodiac cycles and moon phases were likely taken into account.

The slow aging not only enhances and matures the sound — any instrument maker I’ve met speaks about wood as something alive, or peculiar at the least. It seems to have its own spirit. Sometimes, a resting instrument splits or leaks: like a body rejecting a donated organ, the wood can “refuse” the form it’s meant to grow into. For every pipa made, there are many wooden corpses that never make it into their final form. All the more valuable are those that do.

While the craft stirs a certain kind of awe, so does witnessing this instrument spark a sense of reverence, a sort of humility that expands and deepens through uncovering its origins, and everything that is attached to the genesis of music altogether:

Where does the pipa come from? How did people know how to assemble, rest, and play a piece of wood to this kind of detail and perfection?

What does its evolution on the Silk Road tell us about migration of thoughts and peoples? What does it reveal about historical views on the purpose of music, song, and cosmology?

Listening to Cinnabar: A Li Bai Favourite & Putting Grief to Song

In ancient China, music was referred to as the Eight Sounds (八音), and classified into metal (金) – bells, stone (石) – chimes, silk (丝) – stringed instruments, bamboo (竹) – flutes, gourd (匏) – Sheng, clay (土) – xun (an ocarina), leather (革) – drums, and wood (木) – zhu. An instrument is an expression of the elements interacting, of qi flowing. Hence, our qi can change by listening to their music.

The context of music from the Silk Road is vast and rich, and each kingdom, religion and empire tells a story through the sound, body, and the hands playing and crafting the pipa. In a world in which conformity of capital and culture threatens us all, we can become part of a dialogue that has varied intentions — in which political, cultural, cosmological, and religious agendas meet, and in which we can restore the significance of a lute by really listening to its music.

As a first introduction, pick where you want to start. Both pieces unlock pipa music in different, yet intimate ways. I’ve tried to select two pieces that focus on the instrument rather than demonstrating the elaborate and sophisticated techniques pipa music is nowadays known (and intimidating) for.

Click the picture whenever you’re ready!

Both pieces are short, so I hope you come back to listen to the other one.

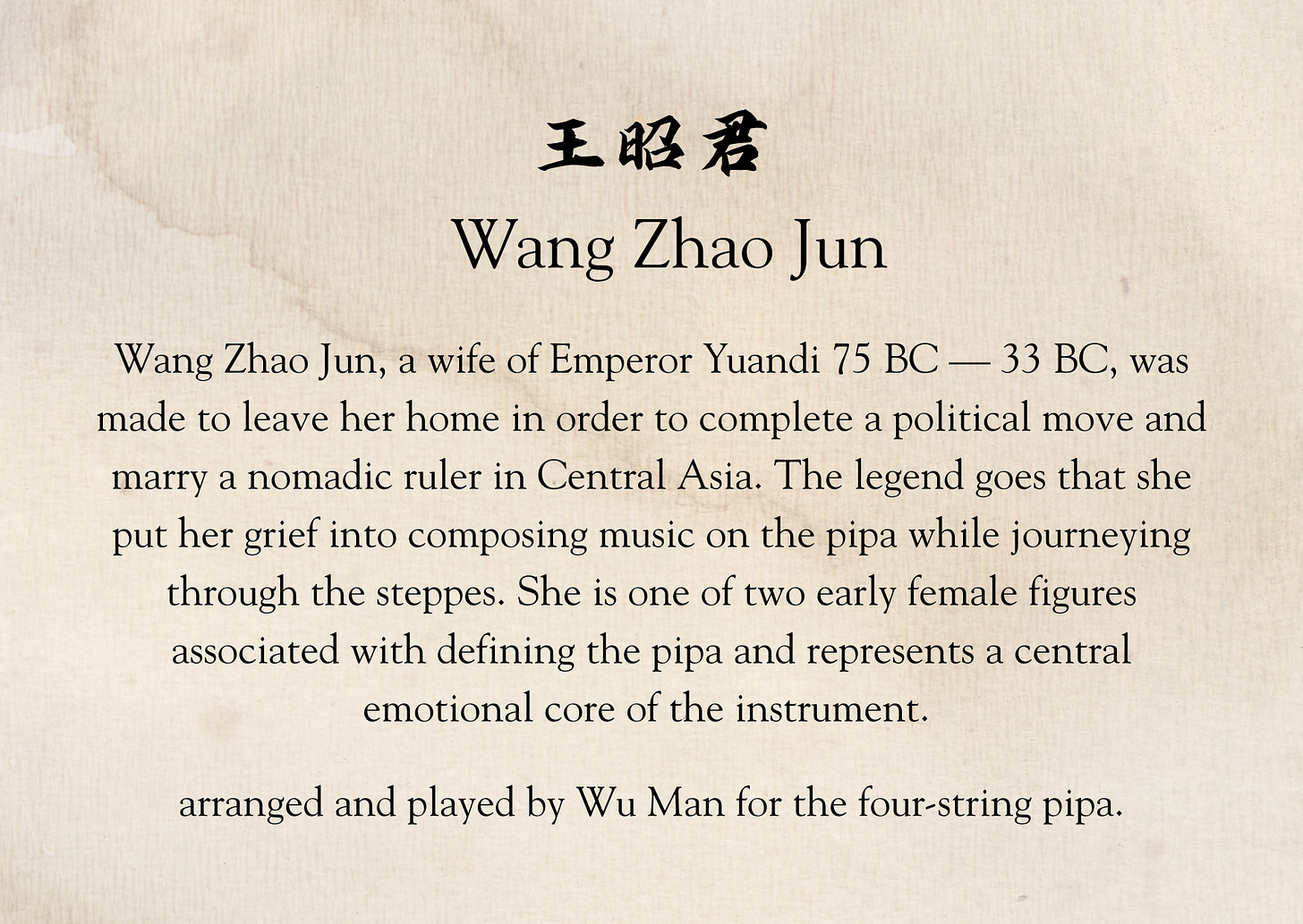

1)

2)

How was it listening to these? Does any part, element or instrument sound familiar to you?

What else can you perceive while listening?

Visual impressions, ideas or thoughts?

Or just an alertness without a feeling?

Knowing that there is context to be provided on how these arrangements came to be, and what possible connection they might have to their “original” (if such a thing exists…), I want to leave you with your impressions for now.

Tracing the roots of sound

Let’s start simple. Because of its onomatopoeic name (pi - plucking outwards, pa - pulling the string inwards), the historical context of the pipa lights up some parts of the map along the Silk Road. As such, the pipa is related to the Persian “barbat”, the Korean “bipa” and the Japanese “biwa”. Like Buddhism, the pipa travelled East: ultimately originating from West Asia, it reached China by the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) and was then introduced to Japan from there, where it became known as the biwa around the 8th century. The biwa, as opposed to the typical pipa now, has five strings and a neck that arches backwards with the head of the instrument facing the sky.

For centuries, “pipa” generally referred to lute-type instruments that varied in size, shape, and number of frets / strings1, but the five-string pipa (五弦琵琶) and the four-string pipa (四弦琵琶) dominate history because of their importance within the High Tang era at court.

Both of these subtypes initially entered China via the Silk Road — the four-string pipa from Persia, the five-string pipa from India. Although the four-string pipa is older than the five-string pipa, both existed in parallel under Emperor Xuanzong’s reign (712–756 CE) in the Tang Dynasty — who was a major fan of the instrument and music from all over Asia altogether. Many foreign musicians from cultures that shaped the pipa anyways were invited to court in order to entertain the Emperor and contribute to the cultivation and education of musical genres.

This led to the treatise of the “Ten divisions of music”: 十部乐 (shí bù yuè). This imperial music categorisation grouped different music types and ensembles. Aside from “banquet music” and “clear music” (Han-Chinese music), a large portion of these divisions include names that classify music with their kingdom of origin. Amongst them, the music of the Kuchean kingdom (a former Buddhist kingdom located in present-day Xinjiang), the An-Kingdom (Sogdian-Persian territory), as well as the Kang kingdom (another Sogdian area) are explicitly listed with the 5-string pipa as part of their ensemble.

This meticulous classification and the initiative to teach and spread the music style of other kingdoms proves how highly these immaterial “goods” from the Silk Road were regarded in the culture of the Tang Dynasty. Actually, this highlights all the more how during this time of the Tang era, “exoctic” art forms were absorbed and preserved next to native art forms. Imagine if any European king in history had issued decrees to include a range of foreign religious music in their court repertoire, as well as dedicated royal funds to further cultivate these lineages at a school aimed at training girls…

In the city of Chang’an, the imperial capital and main Chinese station of the Silk Road, there was a flux of foreign artists everywhere—

There was Pear Garden, the first Imperial academy for music and performing arts that predominately trained female artists for the entertainment of high guests, founded by Emperor Xuanzong himself.

There were tea houses with where Sogdian performers danced to tunes played on the pipa, and courtesans reciting poetry songs accompanied by the pipa.

There were blind monks wandering the streets, chanting Buddhist songs to five-stringed lutes. And there were travellers in caravanserais, storytellers on horse back that found company in the pipa on endless roads.

For whatever reason, the five-string pipa disappeared in China after the Tang Dynasty, possibly in the aftermath of the Lu An Shan rebellion that sought to “cleanse” China off foreign influences. Interestingly, the Chinese language also shifted from having five tones to four tones — though possibly a bit later with the rise of the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368).

Immeasurable Light

The year is 838. Fujiwara no Sadatoshi, a musician from Japan, has just completed an intensive three-week study period with a well-known pipa master, Lian Chengwu, in the ancient city of Yangzhou. At the closing ceremony held by the Kaiyuan-temple, Sadatoshi is personally handed a set of “tuning-tablatures” for the pipa.3 As part of the last Japanese diplomatic missions to Sui and Tang China that also included the Buddhist priest Ennin, Sadatoshi leaves China with these tablatures and takes them home.

Little did he know that some thousand years later, a Daoist monk would discover the main chunk of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, part of a forgotten set of cave temples that thrived in times of the Silk Road and pre-Islamic Central and West Asia, and gradually declined after the Tang Dynasty.4 Among the discovery of thousands of documents, statues, murals, and paintings that drew archeologists from the West and sparked a series of trades and thefts, there is a set of 25 tablature notations of song-melodies written for the pipa.

Little did Sadatoshi know that this set of tablatures, dating back to the early 10th century but possibly documenting a much older performance practice, was written in a strikingly similar way to the tuning-notations given to him by his Chinese teacher. This similarity allowed scholars and virtuosos to contextualise the Tang roots of Japanese biwa music with its Chinese ancestor. Through this key source, the musical legacy of the pipa could be restored not only in terms of its Sino-Japanese relations, but indeed of many Central Asian cultures that were erased or lost to religious wars, ethnic cleansing, and time.

In the early 2000s, pipa virtuoso Wu Man and Rembrandt Wolpert begin interpreting pipa music anew. Utilising Sino-Japanese sources like Sadatoshi’s notations and other togaku sources (Japanese documentations of Tang court music) as well as historical Chinese sources, Wu Man arranges and composes a total of 14 tracks. Rembrandt states:

Modern musical reconstruction and revival of old musics of China (and Japan) ought to follow the same principles demanded of reconstruction and conservation in archaeology, architecture, and visual art. All restoration needs to be reversible, and conservation must be suitable in the historical context of the artifact. […] And to this we add our concern for the protection of the Tang Music legacy as the cultural property of its own tradition.5

The tracks listed at the beginning of this article stem from this venture. And perhaps that’s it — the restless part within me being reached by watching instrument makers bringing objects to life that we are still discovering, that are still ever mysterious, and lush. A part that calms and unfolds as the historical threads hidden within the pipa are unearthed, and one that remains awake and alert to those that light up the Silk Road’s legacy once more, to make it their own.

I think I want to know how continents have shaped an incorporeal dialogue into objects and music.

Thanks for reading so far, and sorry for the delay of this month’s musings. Tell me what you thought of the pipa! Or if there’s another instrument or piece of music that lights up your inner map…

Want to know more about objects and music from the Silk Road, and how they connect to systems of ancient cosmology and even medicine? Subscribe to stay in the loop, and check out Moon Rabbit Musings.

Notes

“Chinese Music - Song and Yuan Dynasties (10th–14th Century).” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/art/Chinese-music/Song-and-Yuan-dynasties-10th-14th-century.

“Biwa: Japanese Short Necked-Lute. Biwa Craftsman Katsuyoshi Ishida” Techniques That Support Japanese Performing Arts, vol. I, 2023. Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties.

Wolpert, Rembrandt, and Wu Man. Wu Man - Immeasurable Light. CD, Traditional Crossroads, 5 Oct. 2025, wolpert.hosted.uark.edu/ImmeasurableLight.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2025. Liner Notes.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Mogao Caves.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Dec. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogao_Caves. Accessed 25 July 2025.

Wolpert, Rembrandt, and Wu Man. Wu Man - Immeasurable Light. CD, Traditional Crossroads, 5 Oct. 2025, wolpert.hosted.uark.edu/ImmeasurableLight.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2025. Liner Notes, emphasis mine.

Further Reading & Watching

Two-part documentary on the recreation of the five-string pipa by Cao Wei Dong:

VideoChinaTV. “China Icons: Five String Pipa Episode 1 中国符号:五弦琵琶 上.” YouTube, 12 Oct. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUF_UH0SsTQ. Accessed 25 July 2025.

Liu, Shuang. “The Artistic Features of the Rebounding Pipa Flying in the Dunhuang Cave 112 Murals.” Frontiers in Art Research, vol. 3, no. 3, 2021, https://doi.org/10.25236/far.2021.030313.

Stunning instruments. I will save and refer back to this as the pipa comes back up in my travels. 🙏

Thoughtfully crafted and a fun read I am always tracing the roots of sound always in process of my Mvskoke language recovery teachings and lessons all of our language is built on sound tone changing meanings- I have made all sorts of instruments from random objects- traditionally we use turtle shells filled with pebbles strapped on our calves for ceremony- it’s very crucial to understand the strongest sounds coming from which shells and turn those towards the fire -we circle in prayer usually overnight- really dug the article-