Tongue Within Heart: Speaking the Ineffable

What happened to the heart? Part IV: Cordelia.

Between your intention and consciousness of your body, there is a language, ineffable, as we call it: not translatable into the realm of words.

It can translate, however, to a one-sided pain that is getting less and less, or a feeling of weight transforming into lightness, or anything that your body expresses through you.

Energy is communication, just as emotion is our universal language.

— Harry Uhane Jim

Happy (belated) New Moon and welcome to the last part of the “What Happened To The Heart”- series. For this New Moon, I’ll be sharing some of my own poetry in the last section of this post. I’m also opening submissions for the next full-moon gazing Lunar Poetry Gathering. The invitation, along with the prompts, will be waiting for you at the very end. I hope you like them!

The tongue is an elongation from the heart. What sounds poetic is as much poetic as it is scientific. As a painting of a person’s inner state and a sensory muscle where many meridians run through, the tongue has become an integral part of diagnosis in Classical Chinese Medicine since at least the Yuan Dynasty.1 It is both a muscle and an organ, after all, and in diagnosis, is treated as such, which means that it is given appropriate attention to interpret its signs and symptoms.

Its colour, shape, cracks, and veins reveal what type of foods a person has eaten, whether there is heat or cold, dryness or dampness in the body. The tongue also indicates the state of blood, qi, and emotions. Everything that encircles our inner world, over time can manifest as a symptom, eventually showing on the canvas deeply associated with the heart: the tongue.

The tongue-heart connection is surfacing in Western medicine, too. A 2009-study revealed how the effects of tongue positions affect the mandibular muscle activity and heart rate. Interestingly, there was a significant reduction of heart rates found when the tongue was positioned to the palate — interesting because this tongue position is held throughout some forms of Buddhist meditation.2 Similarly, a recent study compared the existence of various microbes on the tongue in people with and without congestive heart failure.

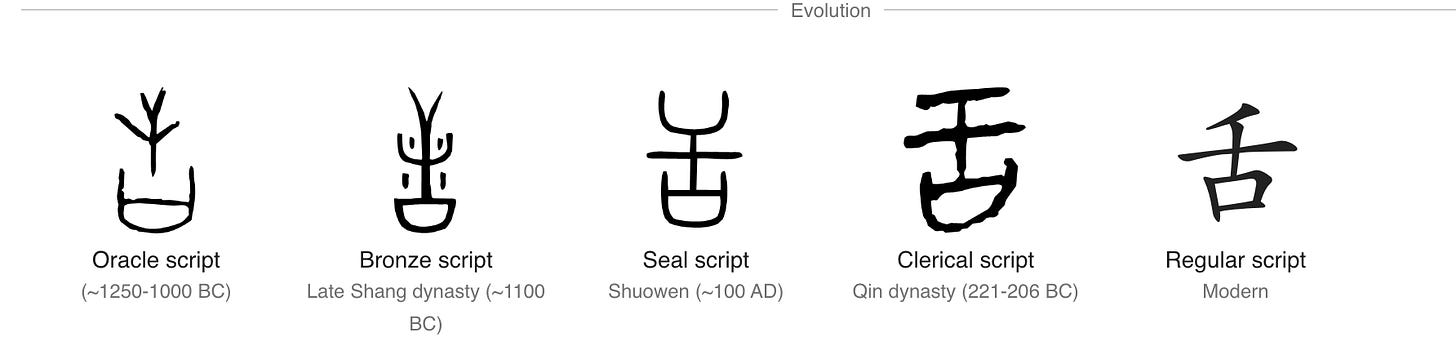

As a mirror to the intelligence of the heart, the tongue symbolises communication. In its first iteration on oracle bones, the character for tongue also indicated the bell and clapper with which messages were announced across towns.3

In Chinese medicine, the tongue is the messenger of the heart while the pericardium is its protector. To those that have something to say, the thought begins in the heart as a need to verbalise. The tongue releases words as much as it swallows them down. Where acts of communication were censored, especially in the history of women, what tongues could not express was stitched into cloth, woven into carpets, embroidered onto silk. “Tongue” therefore also reveals where verbal transmission might fail us.

Mother’s Tongue

Communication can be muddled. Words can seem strange. Tongues twist. Languages must be learned, or even mastered, before we get the sense that we can appropriately express ourselves and even then, words might never do us justice. Or we them.

“Tongue” is as much the flesh of my body that helps me form unsaid words to speech as it is the language I utilise in this process.

“Tongue” is more archaic than language. It doesn’t mean what’s activated in the temporal and frontal lobes of the left brain hemisphere because it predates our understanding of that. Rather, tongue belongs to the pre-verbal world of need. The tongue does many things before we speak: In babies, the tongue-thrust-reflex helps them latch onto the nipple when fed in the first months after birth.

My mother’s tongue. The tongue she shared with me when I was growing inside her, the tongue that’s been shared with her when she was growing inside her mother, and so on. There is a prenatal aspect to tongue, something given and carried, spoken and passed down. Something we begin to channel and actively form as children to build a bridge between inside and outside.

But things are more complicated nowadays. I have a mother’s tongue, and one that I’ve adopted. And so, my tongue changes depending to whom I speak: I address my parents in their tongue and my peers in another. These languages can bring us closer and alienate us at the same time: they can even bring out different personalities.

Between brain and heart, our tongues can also change: ever heard of the curious phenomenon of Foreign Accent Syndrome (FAS)?

The condition can occur, in rare cases, after a stroke (which is seen as the primary cause) and cardiac arrest. A person with FAS suddenly presents a different rhythm, tone or pattern of speech that can be interpreted as a foreign accent. There is a notable case of a British woman who began to speak with an Italian accent after a stroke despite never having had any touch points with Italian language or culture before.4

From a Chinese medicine point of view, we’d say that there is a disturbance of the heart’s control over speech, possibly due to phlegm or wind pathogens from the stroke.

Words, Ineffable

Those who know do not speak; those who speak do not know.

Dao De Jing, Chapter 56

The heart knows, the tongue speaks. Yet, there will almost always be a part in us that remains ineffable. Silent in the realm of words, loud in another.

Perhaps this perspective, inspired by the Harry’s Hawaiian perspective on Ineffable quoted at the very beginning sheds light on what is meant by “those who know do not speak; those who speak do not know”. The Ineffable is for us to keep and harbour, and maybe only us. It’s that part of us that doesn’t explain or justify, that we do not owe, that is expression for us to witness and beyond that, perhaps never anything.

The Ineffable is a component of our sovereignty.

Culture and social codes generally place linguistic skill above authentic expression or authentic silence. We are prone to interpret someone who uses words sparsely as “rude” while someone who engages a lot verbally as “nice” or “interested”. We might be wrong or right about somebody’s intention to be silent or talkative, but this is still the general vein.

While I’m sure that this problem might arise in any culture, the Chinese culture has definitely had this problem since long ago — and by long I mean the Laozi and Zhuangzi kind of long ago. Since Daoist thought guards the inherent nature and spontaneous expression of everything, forced speech was seen as an exhausting abstraction from the realm of artificiality.

In my personal experience, the preference of artificial construct or expression over an authentic one is most destructive and harmful in performative acts of filial piety. It is not easy to live up to protocols of love and gratitude, especially not if our refusal to take part in such a protocol is seen as a direct offence.

In an exhausting game between what’s said and what remains silent, I see a stunning parallel to what’s seen and invisible. The Ineffable goes into and beyond everything on the shadowy side of the hill5, or what’s deep in oceans wide. Everything in darkness supports the life in the light.

While thinking about these dynamics, there are some stories that circle my mind over and over in exploration of how we meet, or fail to meet, expressions of ineffable. My top three are: Spirited Away, Orpheus & Eurydice, Cordelia.

While I will retain my thoughts on Orpheus & Eurydice for now, I’ll end this post with a Shakespeare and South China inspired narrative poem.

Cordelia, From Her Heart

— A Chinese Interpretation of King Lear, or: Fathers, Be Good To Your Daughters.

i.

I could not heave my heart into my tongue: unspoken like now, this line still rings true. I cannot heave my heart… harbours and grows Her, Cordelia. She that heaves nothing: no Heart— no words.

Of your world I know nothing— say nothing, too. When you raised us, Baba, we spoke your tongue, but look at us now, see how we sink; By the time we reign we’ll not remember a thing: the sound of your words will be a cultural song, a tune we’ll dance to when we miss our home.

We came so indebted, that I know. Mother laboured and father paid the fare, So I owe. Since wars, droughts and civil strife drowned blood lines in blood, sank cities to seabeds, took mother from child, broke husband and wife– I owe him. For a worth I do possess but do not own, I owe, “Mylord, for begetting.”

But as I said: I could not heave my heavy heart to grace the numbness in my tongue. I love you, according to my bond, not more, not less. My father I love, but my lord I refuse. Fathers are made and daughters disowned. Father remains, Cordelia goes.

ii.

Begot and uprooted. New soil, as soon as I began to sprout into earth, there you were, Baba. Father. Put me away for not speaking, living, according to my bond, to heave and claim my heart, my home, my lord. There you were, Ba, uprooted yourself, and you spoke.

And you promised, Ba, to claim and own again What they had taken, without a fight, by an attempt to catch the dragon’s tail. And you lost it, Ba. Came to find it here– and I found it, Ba, earned it, too, will earn– The crown you deserve back home I will earn.

Hope: “希望”. That was hope, she that heaves heavy Nothings, Cordelia, was “希望”, his hope. The mother patching her son’s uniform to return him to war lives on hope, like father forsaking Cordelia still yearns.

I should have come to take on your fight: I will keep it safe, the land, have her teach me again how to sound mother’s tongue and her words. Make her flourish again with bright lakes, have her breathe again with clear lungs. Father can leave all of mother to me, her memory.

iii.

Her legacy. Claimed by those who advanced their victory. Spouses of sisters, women who lost their identity. “My lord”-- their world. “My heart” – their will, “My home” – their prize, to be paid, to be won, to be worn out, paid for by an old man who once forsake.

And regrets. What he gets he gives me—life and regrets. Take it from me, father, take regret, it doesn’t fit her legacy, I never saw what home could be, kingdom ours, it was never meant to be. Dragons kicked into tales of creation myth--

But our queendom comes from a goddess’ hip: a mountain shaped like her lovely pear, the lake a mirror to her clouds of thought and rain they would, to please the god of drought. Gemu was everything, and you forgot, How could this loss, never mourned, be so drowned?

His heartache I only taste, and with my eyes see how he cries, does he know how to mourn? Father yelps and swallows and puts it down. Grief does not satisfy. The circle persists, How many orbits more does mother fit? Mother expanding, Cordelia is free.

Perhaps this is her last gift to me. This memory: garden, brink of spring, new moon only hours away. Unfamiliar sight, Unfamiliar sunlight in his eyes. Father’s not gone. Rage relinquished; grief undone; Nothing remains as nothing’s unsung.

Invitation: July Buck Moon

It’s time again! You are herewith officially invited to Moon Rabbit Musings’ 2nd Lunar Gazing Party — join with a piece of your poetry!

The post itself will be published on July’s full moon, the 10th. Traditionally also referred to as the Buck Moon, since the antlers of male deer reach the peak of their growth around this time.

This Moon’s theme is: The Music of Thunder, and these are the prompts:

Antlers: Growing and shedding.

Male deer loose their antlers each winter/early spring to regrow them in a mightier form, and around this time, they are still covered in velvet. Traditionally, these dynamics are seen as a mix of wood and fire: wood symbolising growth, and fire the Yang quality of the process. What does this growing and shedding process invoke? What is it you shed to regrow in a more refined form? Or, in simpler terms: give me your best poem on antlers!Music of thunder

thunder above earth is a defining quality of this time of year, as there is a release of tension that is resolved through thunder. What do you hear in thunder? Which tension do you wish for thunder to resolve?The Ancestor’s temple

Traditionally, this is a time for celebration and reverie. Ancestors, gods, and goddesses were contacted through dance, rituals, and music. Either real or imagined, can you give me your most celebratory poem on a ritual, dance, or piece of music to offer to your temple?

I hope you like the prompts, and send submissions by July 6th for a chance to be featured!

Notes & Further Reading

Solos, Ioannis, and Yuan Liang. “A Historical Evaluation of Chinese Tongue Diagnosis in the Treatment of Septicemic Plague in the Pre-Antibiotic Era, and as a New Direction for Revolutionary Clinical Research Applications.” Journal of Integrative Medicine, vol. 16, no. 3, May 2018, pp. 141–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2018.04.001.

This position also makes sense from a Chinese medicine point of view, since it is believed that the circulation of the Ren Mai and Du Mai, two extraordinary meridians running through the front and back of the spine, can be closed by placing the tongue against the palate.

Kirschbaum, Barbara. Atlas of Chinese Tongue Diagnosis. Eastland Press, 2010.

Foreign Accent Syndrome: “A Stroke Left Me with an Italian Accent.” 22 Dec. 2024, www.bbc.com/news/articles/cdd6r7y33n4o.

In the earliest explanation of Yin and Yang, Yang was seen as the sunny side of the hill, and Yin was seen as the shadowy side of the hill.

this was a lovely article, and your poetry is quite excellent! glad to be a new subscriber of yours!